Undoing Cricket Imperialism

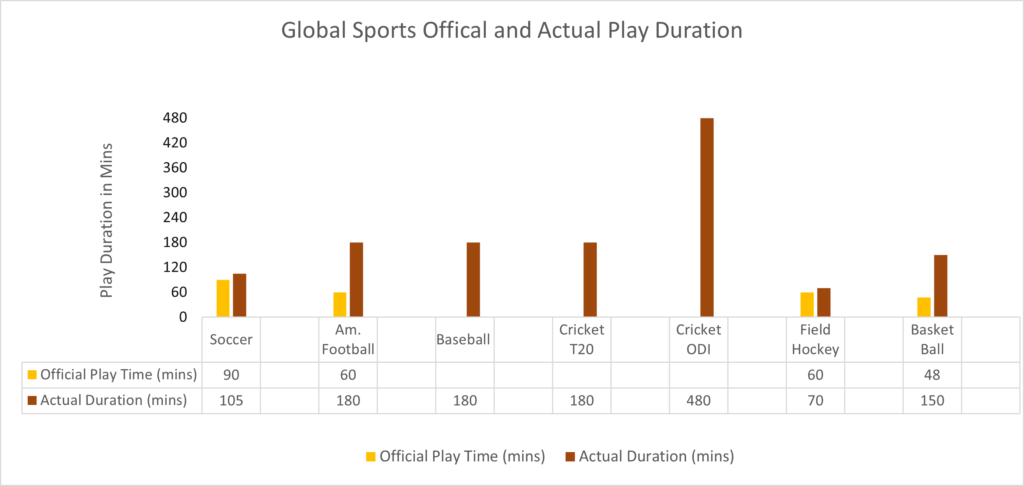

The graph, prepared by Legal Scholar Academy, furnishes official playtime and actual duration for major international sports. Basketball’s official time is NBA.

More than a hundred countries are officially playing cricket, and even the U.S. cricket team is competing in international matches. However, 21st-century international cricket, despite its popularity, has yet to find a global identity. As a contorted silhouette of English imperialism, the International Cricket Council (ICC), which organizes international games, is a practical monopoly of a few powerful nations. To undo this monopoly, the ICC needs a new constitution to promote the fast formats of global cricket without geographical, racial, and gender discrimination. Accordingly, the ICC should discard the male-dominated Test matches played over five days as the eligibility criterion for full membership. The distinction between Test and non-Test nations is an unfair barrier to global cricket. This study recommends that the ICC adopt Twenty20 (T20) cricket, a game of 20 overs, played within 180 minutes, much like other international sports (see graph), as the fundamental basis for granting full membership to the cricket governing bodies.

The cricket geophenomenon, much more captivating than the cricket game, fuels complex enchantment globally, most notably in South Asia. The phenomenon wrestles with cricket formats, racism bouts, and fights over advertisement revenues. Yet, international cricket generates white, black, and brown megastars to everyone’s delight amidst match boycotts, match-fixing, and national rivalries. In numbers of the global audience, cricket is second only to football (soccer) and gaining ground. The 2019 Men’s Cricket World Cup attracted a cumulative average of 1.6 billion viewers. In 1900, cricket debuted as an Olympic sport with only two teams competing, England and France (which knew nothing about cricket). In 2028, after 128 years, cricket will return as an Olympic sport with a wide-reaching competition.

21st-century cricket transcends far beyond England, its weather, culture, intentions, language, and rules, though the England cricket team remains a formidable international competitor. However, the game’s format, dynamics, epicenter, money, power, indeed everything about cricket is changing. For centuries, cricket was a single-nation sport, male by gender and white by race, played leisurely, primarily in the summer months. Cricket is now a global phenomenon, electrifying as heck, running nonstop all year round, empowered by male and female teams of variant colors and races, generating millions of dollars in advertisement revenues. Running commentary is no longer just in English, and unofficial Hindi commentary draws millions of more listeners. The ICC hosts several multilateral cricket competition series of “great pitch and moment” — far beyond Shakespeare’s oration, who probably knew cricket more as a grasshopper.

Cricket Monopoly

The ICC says it strives to “grow the sport by creating more opportunities for more people and nations to enjoy it and increase the competitiveness of international cricket at all levels.” However, the ICC’s existing organizational structure has established a monopoly of a few nations, notably England, Australia, and India, the so-called Big Three. Because it brings huge advertisement revenue to the ICC pot, India argues to have a more dominant say in decision-making and decision outcomes.

The ICC rules establish three classes of participants: Full members, voting Associate members, and non-voting Associate members. (There is a broader trend in economics to divide humans into three categories: upper class, middle class, lower class.). Each cricket-playing country establishes a cricket board as a national governing body free of state interference. These national governing bodies apply for membership to the ICC. Upon reviewing the application, the ICC grants the applicant full membership or associate membership with or without voting rights.

As a lingering effect of Imperial cricket of prior centuries, the ICC Articles of Association do not list but brace the rule that a nation must play “official Test matches” as a qualification for becoming a full member. Currently, ten countries out of 106 members are full members: England, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, West Indies, and Zimbabwe. These Test-nations determine which other nations can become voting or non-voting associate members. The full members’ ratio of 10/106 is a dismal data point.

Imperial Cricket and Racism

Before its name changed to International Cricket Council in 1989, the ICC was Imperial Cricket Conference launched in 1909 to expand cricket as a “civilizing mission.” In the colonial decades, England, Australia, and apartheid South Africa, the founding members of the Conference, dominated “international cricket.” However, the fall of the British Empire changed the cricket dynamics, as India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the West Indies entered the game.

Imperial cricket was class-based as the English upper class identified cricket with privilege, status, style, and snobbery. Ironically, cricket originated in the English villages as a “peasant game.” Cricket as a symbol of Englishness was the cricket played in pastoral lands rather than industrial cities. Romantic literature, including the poetry of William Wordsworth and Lord Byron, romanticized the village cricket rather than the city cricket. The village cricket was a fluid sport with the relaxed bat, ball, ground, and playing rules as the people viewed cricket as a pastime rather than a sport trapped in rigid rules. The Victorians, especially those educated at public schools, regarded the village cricket as “an English form of Christian morality” and fair play.

When the English elites appropriated the game, cricket changed under the uppity culture’s morbid allure with class toxicity. Elite cricket became highly regulated with the standardization of bat, ball, stumps, and the pitch (central strip) between the wickets. Entrepreneurs, bookies, and city gamblers corrupted the game to make money. In elite cricket, the lower classes could still pitch the ball, if at all, but the bat must belong to “gentlemen.” This distinction asserts that batting with style demands artistic expression, apt for the upper class. In contrast, bowling could be aggressive, more suitable to the lower-class temperament. Under the British Raj, the Mumbai Gymkhana, where the colonists and upper-caste Hindus played cricket, allowed an untouchable man named Baloo to bowl without diluting the tradition that the bat belongs to the upper class and segregating Baloo during meal and rest breaks.

In England, cricket was torn apart from its village minimalism, and playing elite cricket now required joining a club: the very concept of the English club was exclusivist, based on social distinctions. “No place in England where everyone can go is considered respectable.” While based in counties, not anyone could join the cricket club, for the working-class “plebians” could not mix, match, and play with “noblemen.” In the 17th and 18th centuries, the English commoners who migrated to the Americas would have no incentive in planting cricket in the New World, as they identified cricket with elitism. Even the Englishness of the cricket touted in the intellectual circles did not sit well with a revolutionary mentality bred with the rhetoric of “all men are created equal.” Deviating from cricket, Americans later invented a more egalitarian (though initially racist) Baseball.

In 1970, an all-white cricket team from apartheid South Africa could not play the scheduled matches in England because the left-leaning newspapers launched a vigorous campaign for an audience boycott. However, the English cricket establishment and then the Imperial Cricket Conference supported the tour. Under public pressure, apartheid South Africa could not play international cricket. However, in 1982, an unofficial England cricket team arrived in Johannesburg to launch a “rebel tour.” The English cricket establishment remained divided over apartheid South Africa until the white minority rule ended in 1994.

Australia, a founding member of the Imperial Cricket Conference, which identified more with the English colonists over the centuries, continues to face racism charges. Officially, Cricket Australia (CA) speaks against racism, but the ground reality is far more complex and tilts toward bouts of racism among the players and Australian viewers. In January 2021, the Indian team playing in Sydney complained of racial slurs, as did the West Indies team in prior years. The Australian cricket team also refuses to take a knee in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Facing intense criticism, the team now makes a barefoot circle before a cricket series to “condemn” domestic and global racism against marginalized groups.

Imperial England succeeded in introducing cricket to its colonies, including Ireland and Scotland. Almost all nations and territories, including Canada and the U.S., where the English had established colonies or the colonial rule, have found cricket clubs, except that the postcolonial clubs could not sustain the class-based distinction of bat or ball. Lord Martin Bladen Hawke (1860-1938), who evangelized cricket worldwide, was a batsman who scored 13 centuries in his life but did not bowl at all. Immigrants and their children like Chris Jordan, Moeen Ali, and Adil Rashid, presently on the England Squad, still have a higher probability of being bowlers than batters, reinforcing the ancient classism that the bat belongs to aristocrats –a custom destined to dissolve in the acid of time.

With the arrival of South Asian immigrants in Britain, some cricket clubs have added racism to classism, just as under the British Raj, the upper-class Indians added casteism to the mix. The Yorkshire County Cricket Club currently faces discrimination charges from a Pakistan-born cricketer who “came close to taking his own life” after experiencing “institutional racism.” England all-rounder Moeen Ali, another cricketer with Pakistani heritage, said there are probably more similar stories of racial discrimination “out there.”

In the early 20th century, cricket in South Asia and the Caribbeans followed the English class model, and the wealthy locals imitated the English customs. The Indian princes, Hindus, and Muslims established cricket teams in seeking parity with the English elite. For example, the 8th Nawab of Pataudi, the ruler of a small princely state in North India, played cricket and his son, Mansoor Ali Khan (1941-2011), the 9th Nawab, became the captain of the Indian team at the age of 21. In line with the customs of English aristocracy, both Nawabs batted. In the Caribbean, colonial administrators, plantation owners, and other whites imported the club cricket.

However, as England wrapped up its empire, the old-fashioned cricket yielded ground to the poor and non-whites who started to invade the cricket space, not in uppity clubs but parks, beaches, and streets. In England, cricket transformed from village minimalism to elitist over-regulation. In South Asia and the Caribbean, the cricket brought by the English elites changed back into village minimalism. Because of this transformation, 21st-century cricket is fast turning into the people’s game worldwide.

Street Cricket

Street cricket, much like English village cricket, thrives on minimalism and rule-fluidity. South Asian “plebians” play cricket with improvised bats, balls, stumps, and flexible rules in city streets and countryside open fields without any “standardized pitch.” Waqar Younis, a world-class bowler, says he started playing cricket at the crop fields in a Pakistani village.

The most striking feature of street cricket is its unlimited creativity that varies from nation to nation, city to city. The poor kids playing cricket in the streets cannot afford to buy expensive leather balls, willow wood bats, and ash wood stumps; they find functional substitutes. Bricks, sticks, even garbage cans turn into stumps, while the local carpenters supply cheap bats made from any available material. The street geniuses invent varieties of balls reinforced with electrical tape to produce the “swing effect” of the leather cricket ball.

In South Asia, cricked has trickled down to congested streets of cities and unmarked grounds of villages, inspiring boys and girls of low-income families to dream of playing in big tournaments. In Lahore, Delhi, Dhaka, and Colombo, teenagers play street cricket without gear, without wickets, with a taped tennis ball as an alternative to a proper cricket ball. Some Indian megastars, such as M.S. Dhoni, Harbhajan Singh, and Ravindra Jadeja, rose from poverty to play outstanding international cricket.

Street cricket represents and perhaps intensifies the interest of the masses in cricket as a sport. Street cricket allows anyone to play cricket: all you need is a bat and ball. Street cricket enables neighborhoods to enjoy cricket for free right from their house windows. It is a mystery why South Asians love cricket more than any other sport. The complex rules of playing cricket fascinate both the educated and the uneducated masses as they absorb the meaning of googly, doosra, cutter, and numerous other key terms. Watching international matches on TV has revolutionized an unprecedented interest in cricket as national teams confront each other in fast cricket, One Day Internationals, and T20 competitions. This interest will deepen further if the ICC shifts its focus from slow cricket to fast cricket.

Slow Cricket

International competitive cricket started as a slow format, called a Test match, played over several days. In a Test match, the two competing teams play two turns (innings) each over five days. The first official Test match occurred in March 1877 between England and Australia. As a custom, Test match players of both teams wear whites and play with a “red ball.” Each day, the Test match is interrupted for lunch and tea, even though playing with a full stomach is a ghoulish idea from a health viewpoint. Few cricketers question that a Test match is considered the highest standard of cricket, a cliché nonetheless waiting to die.

In 1909, the Eton College Chronicle compared slow cricket with football(soccer), noting that a football game “is much shorter and more exhilarating than the rather pompous and tedious” cricket. Test matches “call on a man’s time and his physical strength that a man cannot play cricket unless he has inexhaustible leisure.” Somewhat player-focused rather than team-focused, Test cricket furnishes an opportunity for a single player to make several hundred runs. The West Indies player, BC Lara, holds the world record for scoring 400 runs in 778 minutes against the England team in 2004.

A Test match favors batters who demonstrate their physical stamina to play for hours against bowlers. One wonders if the Test format wafts the ego of “aristocrats” who wish to perfect their playing artistry without pressure to make runs or excite the viewers. By contrast, the ODIs and T20 furnish an opportunity for both batters and bowlers to demonstrate their skill under time pressure.

The Test match viewers must carry a very nourishing view of boredom to sit through slow cricket where nothing exciting happens for hours as the game proceeds from ball to ball sometimes without any prospect for any team to win the match. Even exciting Test matches may run into the rain to end with a whimper. Despite the boredom, Test cricket in England, Australia, and South Africa continue to attract viewers, though not in significant numbers. However, India, the biggest market for any format, does not show much enthusiasm for Test matches even when it ranks as the top world team. Likewise, Pakistan and West Indies play Test matches, but the viewers prefer the fast formats, the ODI and T20.

Test matches are expensive for many nations to prepare players for international competition, and these matches also do not attract advertising revenues the way fast cricket does. Test matches are the least cost-effective format for countries with limited resources.

Most important, Test matches are gender-biased in favor of men. Very few nations send women to play Test matches (4 days), and only England and Australia hold a women Test match annually. The ICC cannot endorse a male-dominated eligibility criterion for full membership. Again, Test matches are outstanding to play for players and even fans, but these matches cannot be the basis for creating a monopoly of a few nations with the resources and expertise to nurture Test matches. By contrast, both men and women national teams play ODIs and T20, and most women teams prefer to play T20.

Fast Cricket

The T20 cricket is fast cricket, and it is the top format for match excitement, fans’ interest, and advertisement revenue generation. Both men and women play T20. If made the sole criterion for full ICC membership, this cost-effective format can bring scores of nations from all continents into playing international cricket, overcoming the distinction between Test and non-Test nations. T20 also promises racial, geographical, and cultural diversity beyond the so-called Anglosphere.

As the graph demonstrates, the major international team sports last for about 180 minutes or less. Even when the regulated time, such as for soccer or ice hockey, is an hour or less, the total time with intervals or other game stoppages does not exceed 180 minutes. Interestingly, the actual action time in American football and baseball is less than 15 minutes. Much like baseball, cricket formats do not prescribe an official time. The Test match can run up to five days, and ODI consumes an entire day as each team bowls a maximum of 50 overs. T20 is the only cricket format that takes approximately 180 minutes for each team to bat and bowl for a maximum of 20 overs.

The T20 format allows working individuals and families to reserve 3 hours to watch a cricket match, mainly when their national team plays in an international series. Sitting for an entire day for an ODI match is relatively trying for working families. Setting aside five days to closely follow a Test match is becoming increasingly impossible even for retirees, especially cricket fans holding day and night jobs.

Of all the cricket formats, T20 is the revenue cow in terms of advertising dollars. Most advertisement revenues generate when India plays as the companies target the vast Indian consumer market to sell products and services. South Asia, consisting of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, plus the South Asian diasporas living worldwide, nearing 2 billion people, furnish the most significant market for advertisements. Ad revenues drop when India is not playing the knock-out matches or the finals.

Among international series, India-Pakistan matches, including T20 contests, generate the most ad revenues. Unfortunately, India-Pakistan cricket is a victim of politics. It isn’t good for cricket when India refuses to play Pakistan out of political considerations, remarkably when Pakistan hosts matches. Indian cricket fans do not wish to boycott matches with Pakistan. Neither do Indian companies, which market products and services to millions of viewers who watch these matches on digital media. The ICC constitution should prohibit political boycotts of bilateral and series matches, except in extreme cases, such as a nation engaging in apartheid or other crimes against humanity.

Cricket-playing countries have exploited the T20 format to establish highly lucrative domestic cricket franchises associated with different states and provinces of the nation. Indian Premier League and Pakistan Super League recruit the most prominent international players each year for vast sums of money paid with revenues raised through advertisement contracts. This internationalization of domestic cricket reinforces that T20 is emerging as cricket’s global identity. The 2021 T20 World Cup just concluded, with the India and Pakistan match drawing record-breaking digital viewing. The next T20 World Cup is around the corner in 2022.

Fast cricket would grow vastly if the ICC could build audience markets in China, the United States, Mexico, Indonesia, Brazil, Russia, and other populous countries. The ICC announced that the U.S. would cohost the T20 World Cup in 2024 — a welcome sign for expanding the boundaries beyond the Test-nations. The revenues for the expansion of cricket would multiply if populous countries could successfully cultivate indigenous interest in cricket.

Conclusion

Cricket is rapidly growing as an international sport as cricket’s ties weaken with imperialism and upper-class, upper-caste domination. Street cricket, much like village cricket in ancient England, has democratized the game in thousands of neighborhoods in South Asia and elsewhere. Because of street cricket, millions of people are fascinated with the game while their sons and daughters play cricket, holding local contests. Whereas all cricket formats generate interest, T20 has revolutionized the game. Most individuals and families with children can set aside 180 minutes to enjoy cricket instead of an entire day for an ODI, let alone five days for a Test match. This interest in T20 multiplies when a national male or female team is playing in international competitions.

The ICC ought to seriously consider making the revenue-generating, cost-effective T20 format, played by both men and women, the eligibility criterion for full membership. Keep Test matches but discard them as an eligibility criterion for full membership in the ICC. This change in membership eligibility would allow many more cricket-playing nations to shape the future of cricket and its management. After granting full membership to most countries, the ICC should hold regional T20 competitions in Africa (21 members), Europe (34 members), and the Americas (17 members). For sure, some of these teams would qualify for and win international trophies. Of course, this geographical expansion would undo cricket imperialism that needs undoing anyways.

By L. Ali Khan