The Politics of Free Speech in Muslim Countries

L. Ali Khan

Political speech, the most significant part of free speech, is anything but robust in most Muslim countries. Criticism of the government lies at heart of the political speech. Ordinary citizens and journalists must be free to criticize public officials, expose corruption in the government, contest policies, even if “those in control of government think that what is said or written is unwise, unfair, false, or malicious.” (U.S. Supreme Court, 1964). Even defamation and libel are unavailable to rulers and public officials to sue and muzzle the critics and journalists.

Many Muslim states stifle the free press, some more than others. Some states own the media and do not permit commercial press, while others allow commercial press but control them through censorship laws. In some cases, the military and intelligence agencies command the state-media and commercial press with hidden hands. In many Muslim countries, journalists disappear, face persecution, imprisonment, assault, torture, and murder. The 2018 assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist whose body was sawed into pieces in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, is the most dramatic example of state-sponsored revenge for exposing the government’s wrongdoings.

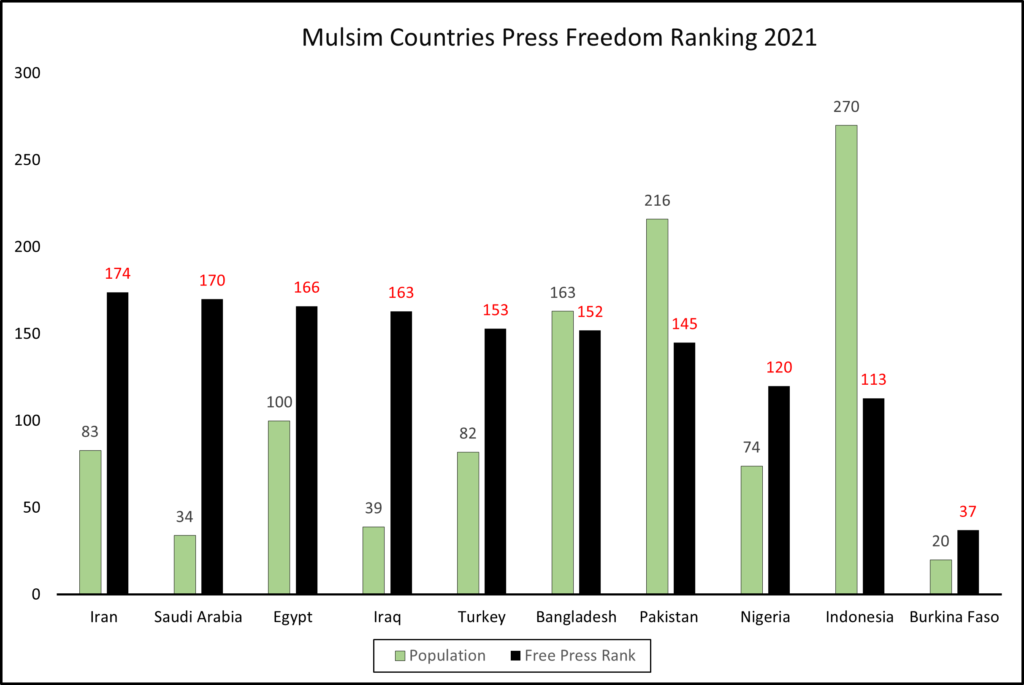

The absence of the free press empowers governments to manipulate the information reaching the people. Globally, the leading Muslim countries occupy the bottom of free press rankings. Out of 180 countries, ranked by Reporters without Borders, a non-governmental organization, Iran (174), and Saudi Arabia (170), the principal Shia and Sunni countries are at the world’s worst. Pakistan (145), Bangladesh (152), and Turkey (153), purportedly constitutional democracies, are slightly better than Egypt (166) suffering under the military dictatorship and Iraq (163) emerging from the U.S. invasion. Indonesia, the most populated Muslim country, trails at 113.

Burkina Faso (37) and Senegal (49), the only Muslim countries in the top fifty, are exceptions among the 57 Muslim-majority countries ranking low. Syria (177), Yemen (169), Afghanistan (122) are worn-torn countries. Even peaceful countries, such as Jordan (129) and Malaysia (119), receive low grades in protecting journalists and the free press.

Political Speech

In the 21st century, free speech is a universal right that allows natural and legal persons to express views under minimal legal restraints. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) empowers the people of every nation “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” The Declaration is binding on all states as customary international law. More than commercial, social, religious, and artistic speech, political speech is vital for the accountability of rulers.

Political speech is inseparable from the notions of popular sovereignty, will of the people, and self-rule. Authoritarianism despises political speech. Political systems founded on power monopolies, such as the military, theocracy, kingship, and cultish heroism, are various dictatorships. Unfortunately, most Muslim states have succumbed to power monopolies, and even constitutional democracies, such as Pakistan and Turkey, punish criticisms of political and military leaders for reasons discussed below.

Political speech musters significance only if journalists in state-media and commercial press can report news and analysis without harassment and injury threats. Unlike ordinary citizens, journalists train in the science of evidence-based reporting, learn investigative methods to expose facts, and report the facts to the public under the guidance of editors and publishers. The corporate press does not always comply with journalist ethics or serve the people’s best interests. Yet, the suppression of news and analysis on the pretext of “fake news” or “national security” or “respect for rulers” (a notion among Arab rulers) is lethal to political speech.

Power Monopolies

Because Islamic law does not mandate any form of government, Muslim nations have instituted diverse forms of government, including democracy. However, since the advent of Islam in the 7th century, Muslim ruling elites invoked dubious religious doctrines to set up power monopolies through caliphates and dynasties. The Muslim empires, including the Umayyads (661-750 CE), the Abbasids (750-1258 CE), the Ottomans (1299-1922 CE), and the Mughals (1526-1857 CE), were dynastic monopolies imposed on the people. Some modern rulers exploit the sacred sources, such as “obey those in authority,” a verse of the Qur’an, to justify their regimes and lack of accountability.

The 21st-century Muslim world is replete with power monopolies. Some rulers blatantly argue that democracy is a Western form of government inappropriate for Muslim cultures, which I discuss in A Theory of Universal Democracy (2003). Some rulers trace their genealogy to the Prophet of Islam to maintain dynastic hegemony. The Iranian clerics have imposed a theocratic democracy, drastically narrowing the scope of political speech. Narcissist authoritarians such as Ghaddafi, Saddam Hussain, Tayyip Erdogan rely on cultish leadership to muzzle political speech.

The mantra of “national security” empowers the militaries to initiate overt and covert power monopolies. Egypt, for example, cannot sustain democracy because the military does not trust the people for electing responsible political leaders. Pakistan is a constitutional democracy on paper, but the military acts as a de facto monopoly behind the parliamentary smokescreen. Militaries launch the propaganda that the nation would fall apart without the generals in control.

In repudiating power monopolies, Muslim populations, politicians, academics, jurists, journalists, and judges need a fundamental shift in how they view elected and non-elected rulers. They must uphold three principles that power monopolies resist: (1) Every ruler is replaceable no matter how good they are. (2) A long tenure for any ruler inflicts more harm than good. (3) Political speech (candid criticism of the government) is indispensable for good governance.

Violence against Journalists

Tied to political monopolies is why most Muslim countries do not nurture a tradition of professional journalism. Political monopolies undermine professional journalism and use a variety of tactics to defeat the rise of independent journalists. Fear-based journalism distorts facts to please power-wielders. In some cases, journalists receive money and other benefits if they report in the rulers’ favor. Consequently, Muslim populations do not trust domestic journalists and see them as crooks who do the bidding of political operators. In Pakistan, several journalists are denigrated as “lafafa” reporters, meaning they receive money to publish favorable stories for vested interests.

Political speech cannot flourish without professional journalism. Just like doctors, engineers, and lawyers, journalists are professionals trained in the science of evidence-based reporting. Even though ordinary citizens, voters, political parties, opinionmakers, academics, and social workers participate in political speech, journalists have access to structured audiences reading newspapers and watching TV. Influential journalists are knowledgeable in the nation’s history, sociology, constitution, and foreign policy. Extensive background knowledge enables journalists to contextualize news and analysis of government policies.

Egypt under military rule “is now one of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists, with some spending years in detention without being charged or tried.” In Iran, under the clerical rule, “At least 860 journalists and citizen-journalists have been prosecuted, arrested, imprisoned and in some cases executed since the 1979 revolution.” Under Imran Khan’s inept government, the intelligence agencies in Pakistan abduct journalists, telling them: “Stop covering unwelcome stories or your family won’t find you alive.”

In Turkey, “the government controls 90% of the national media” and stifles independent journalism by controlling state advertising funds and press cards. Morocco (136) uses “sex scandals” to harass journalists. Bangladesh applies the 2018 Digital Security Law to silence journalists forcing self-censorship. In Indonesia, “the military intimidate reporters and even use violence against those who cover its abuses.” The United Arab Emirates (131) invokes defamation and the country’s reputation to punish journalists who might resort to “very minimal criticism of the regime.”

Judicial Protection

No government welcomes criticism, not even in western democracies. President Trump condemns the free press as “fake news.” A strong judiciary is the bulwark of a free press. Free speech could not have flourished in the U.S. without the unprecedented courage of federal courts in striking down laws and regulations that constrict political speech. Per the U.S. Supreme Court, “Because speech is an essential mechanism of democracy — it is the means to hold officials accountable to the people — political speech must prevail against laws that would suppress it by design or inadvertence.”

Unfortunately, the high courts in many Muslim countries do not protect journalists, a free press, or political speech. There are several structural reasons for judicial reluctance to shield political speech and journalists. In many Muslim countries, the judiciary itself is not independent, and judges fear reprisals for striking down speech-suppressive laws. There is no judicial tradition for judges in some countries to challenge power monopolies, like the clergy in Iran, the royal family in Saudi Arabia, or the military in Egypt. Worse, some judiciaries endorse the authoritarian ideology believing that the country needs “strong leaders” for political stability and economic prosperity.

Take Pakistan, a country where judicial independence is taking root more than in any other Muslim country. The Pakistan Supreme Court has fired two democratically elected prime ministers in daring though controversial decisions. Government institutions, including the bureaucracy, the government, and the Pakistan Election Commission, comply with the Supreme Court decisions. The political system tolerates even hyperactive Chief Justices who assume the administrative authority.

Yet, the Pakistan judges face stiff resistance from intelligence agencies when it comes to protecting political speech. The courts have been unable to safeguard media houses that criticize the military or security agencies. They are helpless in retrieving missing persons, including journalists, who mysteriously disappear. They cannot resolve cases in which influential journalists, such as Hamid Mir and Absar Alam, are shot to be killed.

Currently, a Supreme Court Justice faces possible removal from the court for writing a judicial opinion: He admonished the security establishment and intelligence agencies for acting outside the legal framework. Ironically, the Pakistan President, prompted by the military, filed a reference to remove the Justice. The law minister, a member of the parliament, who temporarily resigns from his office to defend the generals, is determined to see the Justice removed from the court. This example demonstrates how political forces themselves support covert power monopolies.

Conclusion

There is no quick solution to enforcing the right to political speech in Muslim countries where political monopolies are deeply entrenched with multilayered tentacles. Power monopolies resist with force any attempts to challenge their hold on the state machinery. Suppose journalists and judges cooperate in impairing the grip of power cartels; they will face persecution. Nonetheless, true to their respective professions, judges and journalists are mustering the courage to defend political speech more and more. Global media and organizations, such as Reporters without Borders, will continue to shame power monopolies by exposing the abuses they inflict on journalists. Embarrassed power monopolies — clerical, cultish, military, royalty– targeting political speech will likely hide behind religion, even though Islam teaches to fight the establishment of oppression.